Zhang Zhoujie is about to take a great leap. He is set to become the first industrial designer from the mainland to use crowd-funding platform Kickstarter to create a collection inspired by zeroes and ones.

A champion of digitally generated designs, he aims to raise about US$15,000 on the site to fund his stainless steel "digital vessels", which are laser-cut, sculptural pieces with a futuristic bent. His campaign is scheduled to start this week.

I am having more and more failures as I explore new areas. It's kind of an exploration

Zhang Zhoujie, designer

But at Digital Lab, his studio in Shanghai, the 29-year-old Ningbo native is grappling with a request for an interview via Skype. One would assume, because he works closely with computers to produce "logical patterns" to shape objects, that he surrounds himself with the latest technology.

Not so. "I use a camera to control a laser-cutting machine, but I don't have a camera on my desktop," he says with a laugh. "I have a very old computer."

When Zhang realises that the powers of the internet would allow him to show off his studio and creations, he says, "Hang on, I'll Skype from my phone." Five minutes later, he is seen at a large table full of digital vessels.

Zhang sits on a Mirror chair, which can be moulded to the owner's shape

Zhang is perhaps best known for his Mirror chairs, insect-like reflective pieces that are custom made to mould to each owner's bottom perfectly. But he hopes to kick-start his latest collection with an arty, stainless steel tray that, from some angles, resembles the accordion-like throat grooves of a baleen whale.

Kaleidoscopic shapes dominate the rest of his collection. The designs are guided by rules that Zhang encodes in a program, but the vessels also require human craftsmanship, making them unique. A computer-generated pattern is first laser-cut from a sheet of paper, which Zhang folds by hand to create a 3-D shape. The best, or most feasible designs are developed into vessels using sheets of steel.

Although Zhang has produced about 35 different shapes and sizes, he says some two-dimensional computer designs have simply not been possible in 3-D form. "More than 15 - no, more than 100" have failed, he says. "Sometimes we can't fold the shapes into containers."

Little wonder that Zhang's parents baulked initially at his career choice and the desire to go it alone, unlike many of the 10,000 design graduates who emerge from the mainland's 400 design programmes every year to be snapped up by technology firms.

"In the beginning my parents couldn't understand why I would want to work somewhere that's like a factory, when I could have a very good job elsewhere," he says. "But now they realise it's a dream and that I'm in the generation that does what it wants to do. And should do."

Zhang studied at the China Academy of Art and then worked for Lenovo (dreaming up mobile phones) before pursuing a master's degree in industrial design at London's Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design.

In the three years since graduating from Saint Martins, he has finessed what he proposed as a second-year project.

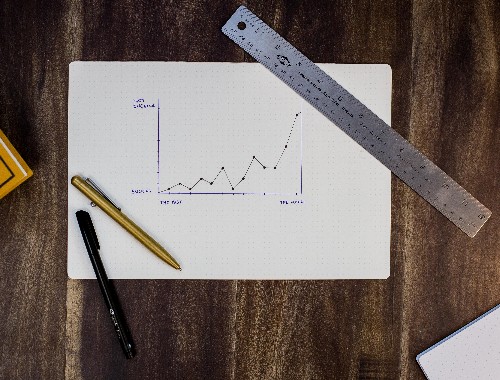

Zhang's computer-generated chair designs

"Some liked it; some didn't," he says, referring to tutors who debated the merits of his computer-generated designs. "One said I needed to make a chair with that typology so people could see how it could be functional."

Which is what he did. But by the time Zhang graduated, his first furniture piece was still impossible to make. "That's why I didn't get a distinction," he jokes.

Any design flaws have obviously been fixed: to date, he has sold 25 Mirror chairs. Bundshop.com - an online retailer and platform for contemporary Chinese design - sells the chairs for as much as US$6,000.

Zhang showcased the chairs at Britain's largest design trade exhibition, 100% Design, in London two years ago. "They sold out in 20 minutes," says Bundshop co-founder Stephany Zoo.

They hope to have a repeat success at this year's edition, starting on September 18. "We will be launching a series of seven vessels [at the London trade show]," says Zoo.

She says his Kickstarter effort will be a first for any mainland industrial designer. "There have been other Chinese designers, but for fashion only."

Bundshop, which is supporting his campaign, will have exclusive rights to the vessels, priced at US$180 to US$250 each.

Price, function and comparative ease of production make the digital vessels more suitable than the chairs for the Kickstarter campaign, both say

"The chairs are always limited-edition and I have very limited production ability," Zhang says, adding that each Mirror takes a month to make. "But the vessels are daily objects and I can produce as many as people need."

The money raised would go towards cutting the production price, he says. "I could ask factories to make more. Right now, I send them one by one … And I could employ more professional craftsmen to help me make these objects."

He employs six people in a three-storey house in Songjiang, Shanghai; the ground floor is his factory, the second his private quarters and the top floor his studio.

On the Skype screen, his assistants can be seen huddled in conversation as their bespectacled boss shows off shelves of products ready to be shipped to buyers, mostly Westerners.

"I combine an Eastern view with Western design methodology, so Westerners understand what I'm doing," Zhang says. "They are willing to have creative objects in their home; in China not many people are into this kind of thing."

But tastes change. Having young designers learn from him, at his studio and in classrooms, will surely contribute to mainlanders' changing artistic sensibilities: as well as two craftsmen and an intern, Zhang employs three assistants from the Shanghai Institution of Visual Arts at Fudan University, where he now teaches "public art" part-time

Zhang's own training began early. He was taught traditional painting from the age of six.

"My father is a calligrapher, so I learned Chinese fine art," he says.

When his father offered to send him abroad, Zhang first applied to the Art Centre College of Design in California but was rejected because his English-language skills weren't up to standard.

Although he made it into Central Saint Martins, Zhang discovered he was befuddled by language of a different kind.

"I didn't understand the weird designs and installations being produced, which to me were not very attractive," he says.

"But after a year I understood fully that design is not just about style or making a certain shape; it's more about the meaning behind the object, the narrative, something deeper."

So what's the story behind his work? "I spent that year clarifying my design philosophy, which has to do with spontaneity and respecting nature," he says.

"Nowadays we can simulate wind, water, natural phenomena. I found digital technology can kind of simulate nature; it's mathematics, and nature is mathematical."

Moving through his studio with his phone in hand, Zhang shows his latest creation - a table that took him three years to develop. Which leads to the question of whether he is experiencing fewer failures now than when he started experimenting with computer-generated design.

"No," he says. "I am having more and more failures as I explore new areas. It's kind of an exploration."

The errors are all part of the toil required to "come up with something important and revolutionary one day". "I hope to inspire many people," he says.

He mentions two industrial designers whose work has influenced his own: Ron Arad of Israel ("he combines art and design") and Ross Lovegrove of Britain ("very futuristic ... and he designs with conviction").

"The older generation have a past," Zhang says. "I can see how they developed their ideas, their path."

He struggles, however, to come up with names of compatriots. "[I can think of inspirational] architects, yes, but industrial designers, no," he says finally, lapsing into halting English. "They are good at commercial products and develop good functional objects. But industrial designers … very deep? No."

That said, Zhang insists he no longer sees himself simply as a Chinese industrial designer.

"I'm not too concerned about nationalities or boundaries," he says. "I see myself as an international designer."

沪公网安备31010402003309号

沪公网安备31010402003309号