In 2014, when the fashion designer Nicolas Ghesquière seated guests on a series of 30 sinuous Pierre Paulin-designed Osaka sofas at one of his first runway fashion shows for Louis Vuitton, he inadvertently shone a spotlight on what was already a growing interest in the late French designer’s distinctive modern furniture created during a career that spanned almost 60 years from the early 1950s.

In the past decade or so, Paulin’s designs have regained covetability, with vintage models snapped up by galleries and auction houses and a 1966 prototype of the designer’s glamorous S-shaped La Declive reclining sofa reaching €300,000 (HK$2.53 million, US$326,000).

One of the most dedicated collectors is the designer’s own son, 38-year-old Benjamin, who, along with his French fashion designer wife Alice Lemoine, and his mother Maia Wodzislawska Paulin, founded Paulin, Paulin, Paulin in 2008 to help preserve and protect Paulin’s creative legacy.

“The greatest challenge for us,” says Benjamin, “is to ensure that my father’s 60 years of creation is recognised. During his career, he continually questioned his designs, reinventing himself every decade, so while some of his best-known creations happened to be realised during the ‘pop years’, he never saw himself as part of any one movement.”

Although attracted at the start of his career by the pure, clean lines of modernist works by designers such as Alvar Aalto, Eero Saarinen, and Charles and Ray Eames, Paulin had an idiosyncratic style that took the form of unapologetically modern, sculptural – yet comfortable – shapes created by stretching brightly coloured elasticated fabric over metal, plastic or wood. “He loved the Eames’ work,” Benjamin says. “Their work with materials like plywood was very inspirational.”

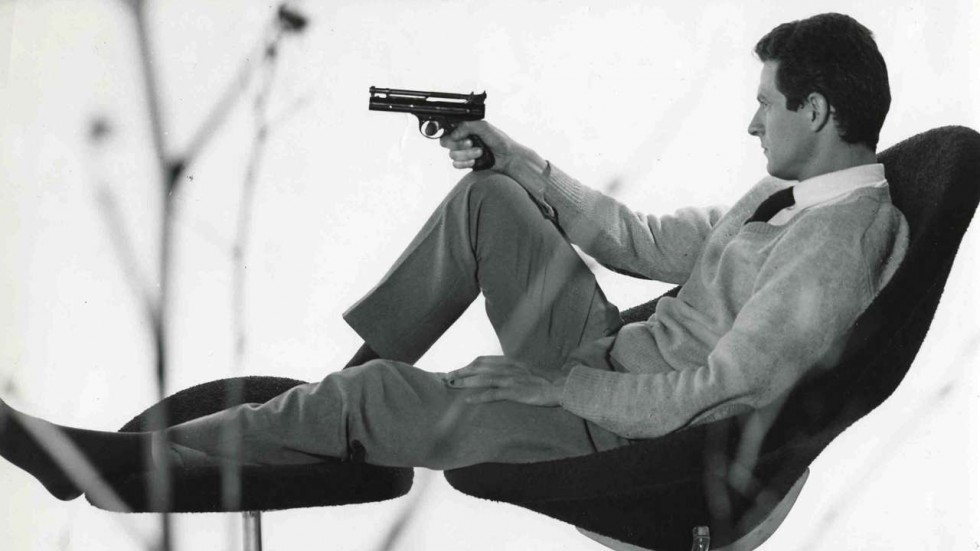

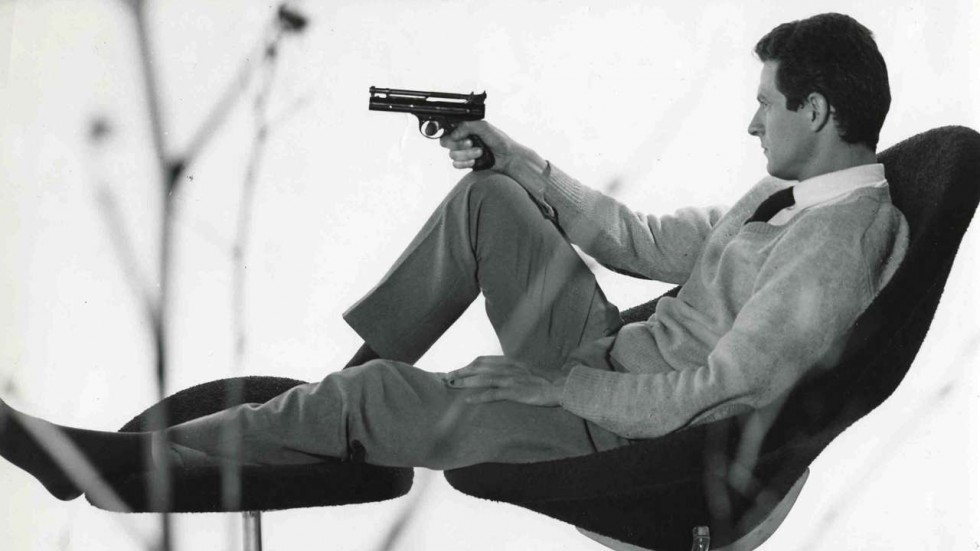

While the designs, like the futuristic 1967 Tongue chair created in 1963 for Artifort, seduced an adventurous post-war France into louche-like lounging upon sensuous forms, Paulin’s focus, says Benjamin, lay primarily with the challenge of addressing functionality and comfort, most notably showcased with his Mushroom chair, developed for Artifort in 1959 and now in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

By 1969, Paulin had become the face of modern French design, with a high-profile commission by the French president Georges Pompidou to redecorate three rooms of the private apartments at the Élysée Palace. Along the way, there were also smaller innovations, like improved designs for electric razors, plastic outdoor furniture and crockery.

In later years, Paulin’s furniture evolved from his early simple organic shapes and modular forms to more complex, artisan-like architectural pieces in wood, such as the Iéna chair. Originally designed in sycamore in 1985 for the Iéna Palace in Paris, it is being released as a first edition by the family. “He wanted to get back to the artisan part of making furniture,” Benjamin explains. “Some of his works like his later writing desks were influenced by traditional joinery but still keep his very simple, pure form.”

Although Paulin’s oeuvre fell out of favour around the 1990s, the current wider revival in enthusiasm for his work is in large part thanks to a major retrospective held at the Centre Pompidou in 2016. The exhibition introduced the public to Paulin’s eclectic career from the 1950s to his death at the age of 81 in 2009, with more than 100 pieces.

Read the full article here: http://www.scmp.com/property/article/2082481/paulins-retro-designs-flourish-splendid-isolation

(Source: www.scmp.com)

沪公网安备31010402003309号

沪公网安备31010402003309号